How to Cook Authentic South Louisiana Rice

New Orleans, my birthplace, and all South Louisiana are justly known for unique and exquisite cuisine. It includes French Creole and Cajun styles that have gained widespread popularity. Cooking is serious business among Louisiana families, and we relish fine dining with each course accompanied by wine pairings. While all three daily meals have special dishes, dinner is most important and often formal with nice linens and tableware. In my family, everyone had to be seated at the table before we began dinner, of course initiated by saying grace. We had to ask to be excused from the table before leaving at dinner’s end.

My mother was the primary chef, although we all made contributions depending on the menu. My sister and I learned cooking from Mother, who was quite accomplished in regional cuisine. My father and brother specialized in grilling and broiling meat and game, which they hunted. Everyone cooked fish and crustaceans, frequently used in our cuisine. Naturally we made all the famous Creole and Cajun dishes: gumbo, étouffée, Creole sauces, grits, rice, and numerous vegetables almost always cooked with ham or bacon. But my family rarely had desserts. My mother never included them, perhaps because she hadn’t learned to bake or wished to avoid additional calories.

According to South Louisiana people, there is a particular way to cook rice. It should be light and fluffy, each grain standing apart from its fellows. If rice was sticky or clumpy, the cook had failed. Rice was an accompaniment to gravy, gumbo, red beans, Creole sauces and étouffée, and the foundation for jambalaya and dirty rice (made with diced giblets). Rice as a base for stir-fried vegetables or pilaf was not part of my family’s meals, although these were not unknown locally. There are variations on “perfectly cooked rice” but I’ll give my mother’s version first.

Steamed Rice According to Dorothy Martin

Bring a pot full of water to a boil. Add 1-2 tsp salt depending on how many servings of rice. Rinse 1-2 cups long grain white rice under running water until it drains clear. Add to boiling water and cook 15 minutes. Drain rice in colander, then place colander over new pot of boiling water. Cover colander and steam another 5-10 minutes until rice is fluffy and each grain is separate. Now you have perfect rice.

That may seem like a lot of effort for rice, which many people just put into a pot in 1-to-2 ratio with salted water, bring to a boil, lower heat, cover and cook 20 minutes. But I guarantee you, the results will be different. Some Louisiana cooks use variations of Mother’s approach, boiling rinsed rice in the pot until the water is absorbed, then turning off the heat, covering pot and steaming until rice is done. Proportions are 1 cup rice to 1 1/3 cups water.

In the interests of “full disclosure,” I admit to using the easier boil in a pot method now. But I do miss the special texture of my mother’s steamed rice.

What to Serve With Rice

Everything from roast beef and gravy, duck or seafood gumbo, red beans with Andouille sausage, and shrimp or crawfish Creole goes well with your perfect rice. Today I’m featuring shrimp étouffée to serve over rice. Crawfish étouffée is the classic dish, but getting crawfish is not easy outside of Louisiana. The dish has a curious history. Originally it was known as crawfish courtbouillon, a rich stew of seasoned “Holy Trinity” vegetables—onions, bell pepper, and celery. Crawfish tails and fat were added after the stew thickened. In late 1940s, the owner of a Lafayette restaurant was preparing the dish at home, while a frequent customer watched. In French the customer asked what was being prepared, and was told “smothered” crawfish—étouffée is French for smothered. Later at the restaurant the customer came with friends and ordered “crawfish étouffée” coining the name by which this dish is now known.

Shrimp Étouffée

Modified from Talk About Good!

1 lb. raw peeled, deveined shrimp

¼ lb. butter (or mix ½ butter – ½ vegetable oil)

3-4 tbsp. flour

1 cup each chopped onions, celery, and green bell peppers

Salt, pepper, chopped parsley, chopped green onion tops

Melt butter/oil in deep skillet, add onions, celery, and bell peppers. Sauté until softened, sprinkle flour over and mix well, cook to form light colored roux (gumbo or gravy base). Add salt, pepper, and parsley to taste. Add 1 cup water, stir well, cover and simmer ½ to ¾ hour (add more water if needed). Add shrimp and cook 4-5 minutes, until shrimp turn pink. Add more water if necessary, correct seasonings. Garnish with more chopped parsley and green onion tops. Serve over perfect rice.

If you add chopped tomatoes or tomato sauce to this recipe, you turn it into Shrimp Creole. That is also delicious, just a different flavor. These recipes and many more authentic Louisiana dishes are in my go-to cookbook, Talk About Good! Le Livre de la Cuisine de Lafayette. (Junior League of Lafayette, LA, 1969). I wore out my original cookbook after 50+ years of use. Fortunately, it’s in the 33rd printing, available on Amazon. I got a new copy two years ago. Maybe next time I’ll tell how to make roux. Bon appetite!

Three Women on a Porch: Story Behind the Picture

When I became the keeper of my family genealogy site, there already was a large photo gallery. Browsing through, I found this photo of three women on the porch of a French Creole cottage-style house. There was no description, but I knew the house was typical of South Louisiana along the Mississippi River, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The steps and porch looked vaguely familiar, as though long-ago memories were being tickled. From the women’s hair styles and clothes, I placed the photo around 1910.

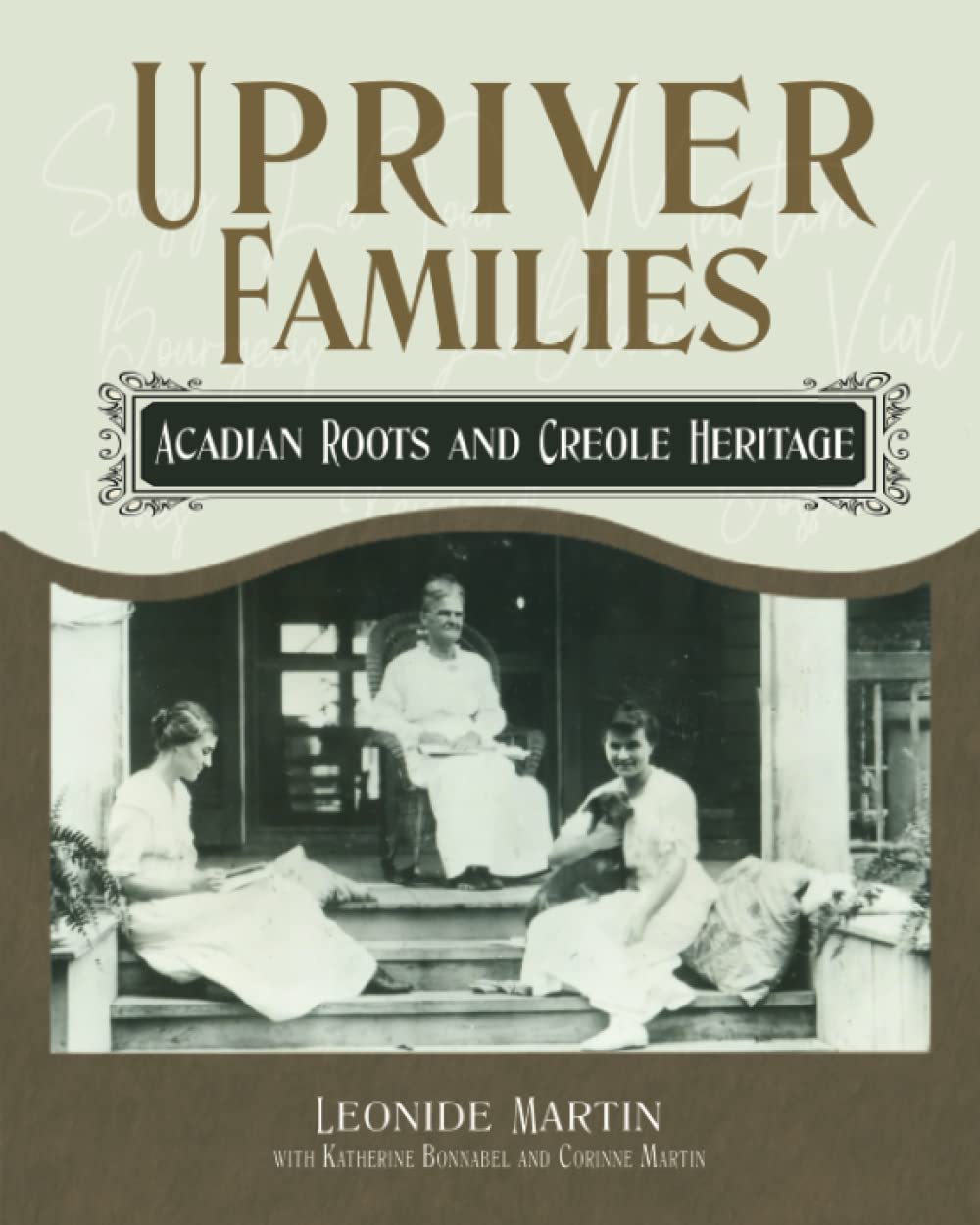

I found the picture striking. The older women in the center had a square face and stern expression. Her eyes and brows resembled others I knew in the Martin family. The young woman at left in the photo had a graceful demeanor and lovely profile, studiously reading her book. At the photo’s right, a sprightly young woman with round face and faint smile held a dog in her lap. She was the only one looking at the camera, suggesting she was forthright and engaging. I was so taken by the picture that I chose it for the cover of my family history book, Upriver Families: Acadian Roots and Creole Heritage, co-authored with daughter Katherine Bonnabel and cousin Corinne Martin.

By then I had discovered who the women were. I sent the photo to several family members, and although there was some disagreement, the consensus was that they were Celeste Triche Martin in center, and her two daughters Irma Martin at left and Marie “Keet” Martin at right. Apparently, the photo was in a collection given to cousin Corinne by our aunt Minerva Martin, the family historian before passing that job on. Corinne remembered Aunt Min telling her the matriarch in the center was Celeste Triche Martin, our great-grandmother and our grandfather J.B. Martin Jr.’s mother. J.B. (Jean Baptiste) was brother to Irma and Marie “Keet,” as well as six other siblings. The source of the photo is unknown.

J.B. Martin Sr. was our great-grandfather and husband of Celeste. He was clerk of court for St. Charles Parish and worked in Hahnville. Celeste’s father, J.C. Triche Sr., was editor of the St. Charles Herald and quite influential. In 1883, the sale of property to Celeste Triche Martin was recorded, it was once part of Colonel Richard Taylor’s Fashion Plantation. He was the son of U.S. President Zachary Taylor. After the Civil War, the plantation was sliced into several lots and sold. The Martin family situated a large two-story house built in typical French Creole style there, set well back from the road with a long driveway. The property was 162.66 acres, a long narrow rectangle extending west from the Mississippi River to a wooded, swampy area and the railroad tracks. The river was the main transportation artery and properties commonly came with river access. River Road was constructed in early 1900s but was rough and muddy much of the year.

The driveway led from River Road past the house to outbuildings including barn, garage, and storage shed. A porch bounded by railings ran the width in front, and plain square columns supported the roof. Central stairs on which the two daughters are sitting led up to the elevated first floor, and the mother is on the porch. Creole cottages typically had living and dining rooms on the first floor, and bedrooms on the second. Behind was an extension containing the kitchen, bathrooms, pantry, and storage. Two chimneys rose above the roof venting fireplaces. Later a three-window dormer was added to brighten the upstairs bedrooms.

Celeste’s husband died unexpectedly in 1897 at age 50, still holding office as parish clerk. Our grandfather J.B. Martin Jr. was 16 years old. Celeste managed the household and raised the six young children, assisted by her large extended family. She lived to see the new century and the success of two children: J.B. became superintendent of schools for St. Charles Parish for 31 years, and Marie “Keet” became a noted teacher, band director, and principal in the public school system for 41 years.

Irma married Leon Charles Vial I in 1902. His family owned adjacent property that was part of Fashion Plantation. He was a leading politician and sheriff for 22 years, initiating the “Vial Era” in parish politics. Holding public office on 10 different occasions, he never lost an election. Sheriff Vial’s sister Leonide Mary Vial (our grandmother) married Irma’s brother J.B. Martin Jr. in 1903. Called a “double marriage” in local parlance, this intertwined the Martin and Vial families in multiple ways. The couples were double in-laws and their children double first cousins.

Irma died in 1913 and Leon remarried the widow Marie Keller, whose family owned Home Place, a nearby plantation. Celeste died in 1924 at age 72. The house on River Road in Hahnville became home of Marie “Keet,” the youngest daughter, and her husband Laurent J. Labry. They adopted two children, grew orchids in a hothouse, and after Marie died in 1981, the house was sold. It was neglected for years, until a Vial family member bought it in 2020. Renovation was begun but put on hold by Hurricane Ida. Now boarded up with stabilized foundation, the old Creole cottage awaits renewal.

Are We Cajuns? My South Louisiana Family’s Acadian Saga

A Story of Origins by Leonide (Lennie) Martin

Growing up along the Mississippi River just above New Orleans, I was surrounded by French culture and language. My grandparents and many family members spoke French, but sadly, I didn’t learn it. There was a campaign to “Americanize” us and English was the language of business and success. Not all French people were alike, and I was aware of status based on education and prosperity. Cajuns were at the low end when I was growing up. My family was toward the higher end. This origins story is about how I was able to answer the Cajun question.

I have French heritage on both sides, but more in my paternal lineage involving the Martin and Vial families of St. Charles and St. John the Baptist Parishes. These families are intertwined with “double marriages” (brother-sister pairs from both families) and cousin marriages that often needed priest’s dispensation. Over generations they were local leaders in education, business, and politics. Their ancestors had arrived in New Orleans and upriver parishes in the mid-1700s from France, St. Domingue (now Haiti), and Acadia (now Nova Scotia, Canada). The Martin-Vial family has lived for seven generations in New Orleans and the Acadian Coast, as the region is called. Entering the 20th century they were professionals, merchants, and large-scale sugar planters.

When I was around eight years old, I asked my mother “Do we have any Cajun blood in our family?” Her response struck me, conveying shock and disdain: “Certainly not!” It stayed in my mind over the years. I wondered about her emphasis on not having any Cajun connections, since South Louisiana is full of them and we have so much French in our family. There were many who identified as Cajun among my friends and neighbors. But, I also knew there was a pervasive bias against Cajuns among my family’s social circles.

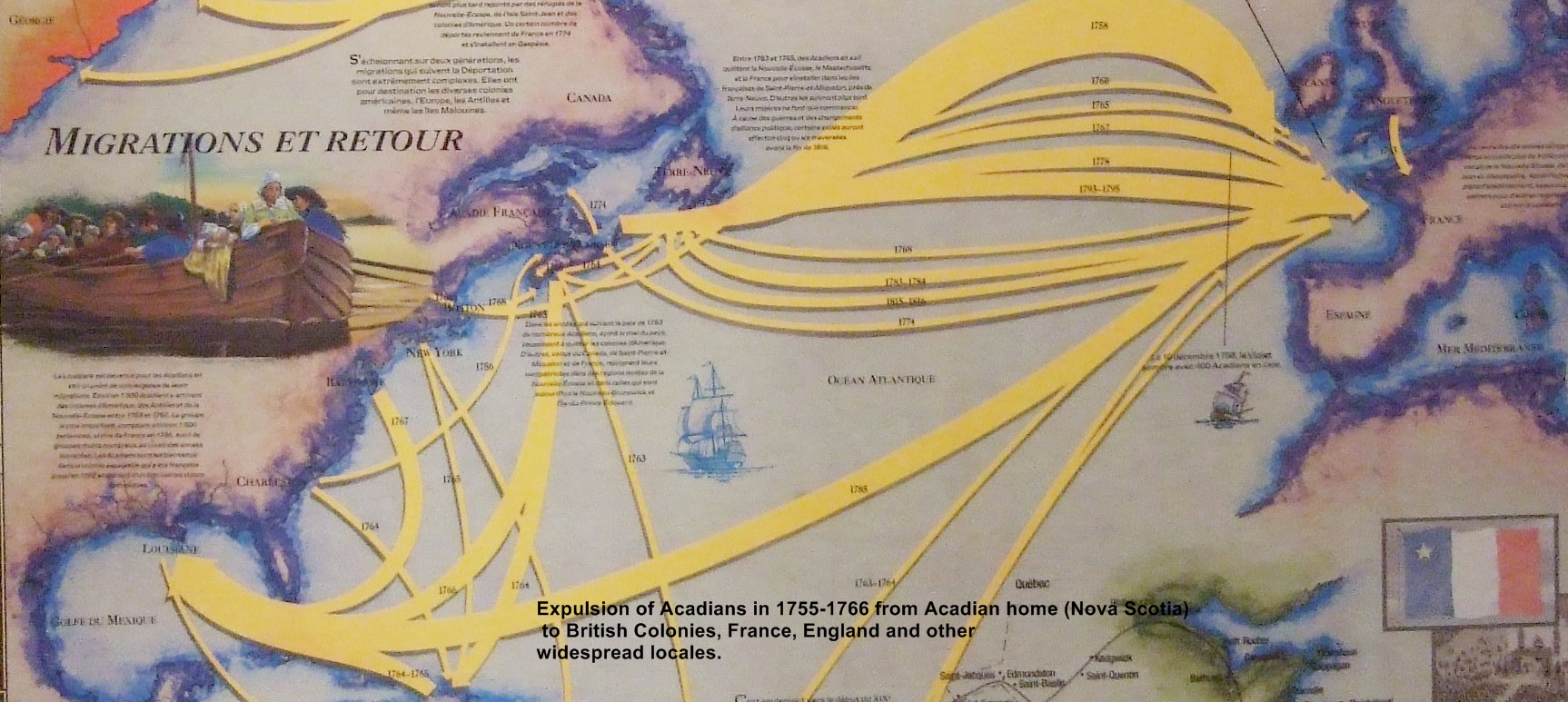

To understand the Cajun issue, it’s necessary to examine their history and cultural evolution. The term Cajun came into use during the early 1900s, a corruption of “Cadien” which is the shortened version of the French spelling Acadien (Acadian). The Acadians were French settlers who came to Nova Scotia in early 1600s, in a region they called Acadia. They created a unique farming culture and prospered for over three generations, reclaiming marshland using a French dike system (aboiteaux) to develop rich soil that made the region a bread basket for Europe. Acadia was also rich in furs and fishing, desirable lands hotly contested among European powers. It changed hands among France, England, and Scotland ten times in just over 100 years. After the final British victory in 1710, the Acadians lived in an uneasy status as French neutrals until their expulsion in 1755. The British wanted to give their rich farmlands to “good English-speaking Protestants” and essentially confiscated properties, shipping over 12,000 Acadians into exile in France and along Atlantic seaboard British colonies, none of which wanted them.

This Acadian diaspora is now considered violation of international law and ethnic cleansing, for which Queen Elizabeth II made amends in 2003. About 4,000 Acadian refugees made their way to South Louisiana, settled along the Acadian Coast and re-established their culture. Gradually they became Cajuns, whose preference for simple living, enjoying life, and tight kinship bonds led to being stereotyped as lazy, fun-loving, and unambitious ignoramuses living in shacks out on the bayou. Two world wars and economic opportunities led to mainstream lifestyles for many, and now Cajun culture is admired and celebrated for its cuisine, music, and festivals.

Over 60 years after I questioned my mother, I was drawn back to examine our Cajun connections. My oldest daughter Kathi Bonnabel had become the family historian and said we had Acadian ancestors. She invited me on an ancestor quest to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, home to large groups of Acadians. Some family surnames such as Bourgeois, Leblanc, Bujol, and LaTour were common there. We made a pilgrimage to places they lived including Grand Pré and Beaubassin, and took part in celebrating National Acadian Day in Bouctouche.

After this, I was hooked on genealogy. I decided to research the Vial family, which had several Acadian ancestors. My maternal grandmother was Leonide Mary Vial, she married J.B. Martin. Drawing heavily on my second cousin Wayne Vial’s extensive Geneanet tree, I traced backward from my grandmother for 11 generations, mostly through maternal lines, to Charles Amador de St. Étienne de LaTour. This distinguished ancestor was a French founder and Governor of Acadia in the early 1600s. His first wife was a native First Nations Mi’kmaq called Marguerite Membertou, daughter of Sagamore (Chief) Anli-Maopeltoog Membertou (Catholic name Henri). From them our Acadian line descended; four generations in Acadia, the last generation was expelled by the British. My ancestors were exiled to the Maryland colony, where they suffered hardships but did better than most, able to depart after 10 years and come to New Orleans. This family settled in Donaldsonville, in Ascención Parish.

Tracing our Acadian roots took nearly 10 years; Kathi and I worked together with help from cousins Corinne Martin and Wayne. Acadians reused given names frequently, finding maiden names was difficult, even surnames overlapped as we discovered two separate branches of Bourgeois, one Acadian and one directly from France. Once in Louisiana, the Acadians married into Spanish and French Creole families. “Creole” was a term used to describe someone whose family was European but they were born in the New World. Eligible daughters to marry military and government men where suitable women were scarce, and upward social mobility were driving forces for this. Marguerite Bujol was the last purely Acadian ancestor; she married Juan Francisco Vicente Chevalier Vives, a Spanish military commander, in 1780. The next five generations continued marrying Creole families and there was no further infusion of Acadian blood.

By my grandmother’s generation, the proportion of Acadian genes was reduced to 3.125%. Culturally the Vial-Martin family was completely Creole and had forgotten our Acadian roots. Even the Creole concept was faint and we were Americanized, with a French twist. My father was 1.56% Acadian and I’m a mere 0.78%. While we can say that we have Acadian heritage, my mother was conceptually if not technically correct—we don’t have Cajun blood, because what remained of it had turned Creole.

But, our Acadian origins remain precious to Kathi and me. Our efforts to trace the family lineage led to publishing a book: Upriver Families: Acadian Roots and Creole Heritage (Made For Success Publishing, Issaquah WA, 2022). The book goes by generations, describing the families, societies, and historic events surrounding each. It also tells the story of how the Vial and Martin branches were separated by a feud during the 1940-50s and got reconnected during our genealogical research. We describe several famous, curious, and notable relatives and their contributions to society. With this exploration of origins and reconnections among families, we are affirming our abiding love for places and people with tangled roots and colorful, complex heritage.

My Big Move

Demented Author Moves to Southern California During Covid-19 Pandemic

Why would anyone plan to move to a different state during the summer of Covid-19 Pandemic? I pondered this question for many months as my husband David and I were deliberating about leaving our home of 13 years in Silverton, Oregon. Oregon is a beautiful state—during the summer, that is. We lived near Silver Falls State Park with 11 stunning waterfalls, and next to the iconic Oregon Gardens. So why choose to leave, especially since we have a nice network of friends?

Anyone who has not endured Oregon winters may well ask why. What we didn’t know about Oregon, having only visited during the summer, was just how dreary and long the winters are. Around mid-September the weather gods turn off the sun switch, relegating the Pacific Northwest to unrelenting months of rain, gray skies, fog, bone-chilling cold, various amounts of snow and ice, and short gloomy days. Weeks of grayness and gloom, moist cold, and persistent rain send me into a seasonal depression (probably the dread SAD-Seasonal Affective Disorder). David isn’t so bothered by that as by being cold all the time, despite keeping the heat going. He huddles with a throw blanket over his shoulders while wearing heavy sweats plus a jacket.

We’re quite miserable during winter, which seems interminable. A few bright days in March or April taunt us, sparking hope that soon dies as rain and gloom return. They say that summer doesn’t arrive until after July 4. It’s often raining on the Independence Day parade.

We tried taking trips during the winters, which works for a few weeks but is a temporary respite. For us, it’s hard to swing for long both financially and dealing with our two cats. So we explored places with sun and warmth during the winter, including Hawaii, Arizona, and California. Love-love-love Hawaii but too expensive and far from family. Arizona might work but didn’t have as much appeal as southern California, where we have family. As former Californians, we’re familiar with the state’s peculiarities and challenges. It was a lengthy process, but we settled on a senior 55+ community called The Colony in Murrieta, CA.

As we’re both well over 55 this is a good choice. Another reason for moving was the new development that sprang up behind our Silverton house over the past 4 years. Initially our back deck looked out over a serene meadow with tall grasses, blackberry vines, and stately spruce trees. We watched deer wend pathways through the meadow and coped with excursions by skunks and raccoons into our yard seeking tidbits. Rather suddenly our little nature preserve disappeared, invaded by clanging and belching heavy equipment digging ugly trenches and scraping away trees and vegetation. What a sad sight! We felt so sorry for animals and the golden eagles that occasionally perched in the tallest spruce.

Quickly there were new streets, house pads, and construction in full swing. Over 40 houses were built, too large for their small lots with painfully repetitious, ugly designs. A cul-de-sac just behind out house attracted a seemingly endless swarm of kids riding bikes, playing hop-scotch, and tossing basketballs into a portable hoop. Our own neighborhood children were never so noisy. Yeah, we’re old curmudgeons but just don ‘t like screeching kids right behind our home—especially during happy hour as we take advantage of the few warm summer days that Oregon has to offer.

Oregon has great wine, by the way. We lived in the Willamette Valley that specializes in world-class pinot noir and other cool tolerant grape varieties such as pinot grigio and chardonnay. But, we’ve not lost access to great wine by moving to Murrieta, twin city to Temecula, one of California’s primo wine producing regions. Due to different climate, Temecula wines are warm weather varieties such as cabernet, merlot, viognier, Spanish and Italian varietals. We’ve already found several outstanding wines such as sangiovese, Montalpulciano, big red blends, and delicious peach-melon viogniers. Not suffering in the wine department! Even joined our first wine club here, Robert Renzoni Vineyards.

The Colony is a beautiful gated community for active seniors with a large pool and nice golf course (we aren’t golfers but there are several in our family). It comes with the usual amenities, such as clubhouse, gym, tennis courts, bistro, and innumerable activities. At present due to the virus, these facilities have limited use and most activities are canceled. Speaking of Covid-19, we were fortunate to make trips for house searching and the two-day moving ordeal without coming down with it. This area of California takes prevention seriously, nearly everyone wears masks, and businesses follow guidelines for social distancing and limiting customers. We are very appreciative of this.

Of course, the noise level around the community is quite low. No more screaming kids! Our back patio feels like an oasis surrounded by tall palms and yew trees giving shade and seclusion. The house stays nicely cool due to thick stucco walls and great air conditioning. Yes, beware what you ask for—we’ve endured two intense heat waves with several days in triple digits. One might say unrelenting sun and blue skies. Not as dry as Palm Springs due to higher elevation (1200 feet), more vegetation, and proximity to the coast about 30 miles west. It’s a reverse weather pattern from Oregon, with two intensely hot months (July, August) and then temperate days with cool nights the rest of the year. Plus lots of bright sunshine.

Well, maybe I’m not so demented after all. Now let’s stay safe and take wise action so this virus pandemic can finally end. Maybe I’ll even get back to writing before too long!

Not much that a good glass of wine can’t fix!

Leonide Martin, Author Historical Fiction

When Authors Must Stay At Home

Most of us are staying home or limiting where and when we go out.

This is an important part of caring about each other and joining together to limit spread of Covid-19 and its harrowing toll of sickness and death. Life as we knew it is suspended for a while. There is much uncertainty about when things will return to any semblance of normal. We’re not able to see our family and friends face-to-face. We keep in touch by social media and phones. Many of us are expanding our comfort with virtual interactions and learning new tricks.

As an author, this “stay at home, stop the spread” reality is both familiar and oddly unsettling. It’s familiar since I already stay home a lot, especially since I’m retired (from a day job) and don’t need to go anywhere regularly. Many of my days were already spent facing my computer screen, doing research and writing. Days could pass without going out anywhere. But when I felt the need to take a break, get some physical activity, go shopping, or socialize with friends, these options were available.

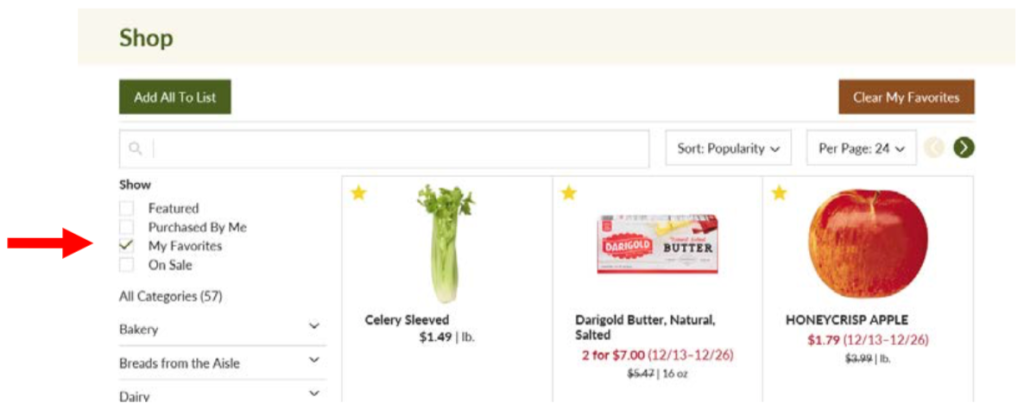

Now they are not. For physical activity, I can take a walk being careful not to approach any other walker closer than six feet. I can do yoga or calisthenics at home—you know just how much appeal that has. For socializing, I can call people or engage in online messaging. That’s OK but not nearly the same as in person discussions. I can do some shopping, but need to put in an online order, hoping what I want is in stock, and set a time for pickup where the clerk puts the groceries inside the trunk. Or else, have things I’ve ordered online dropped off on the porch.

Brave New World indeed!

Now you’d think that an author forced to stay at home would become wildly productive. You envision authors glued to their computers, keying out thousands of words. That new project should be a breeze with so much time. Take on new challenges and spiff up all your social media platforms. Finish those stories. Write amazing blogposts. Submit to awards and contests. Write book reviews by the dozens.

The funny thing is how hard I find it to get motivated. The national crisis has a way of sapping my energy and concentration. I try to avoid watching too much news, but there’s a dreadful fascination with how this pandemic is wreaking havoc across the world. My heart is heavy over such suffering and loss. Silently I urge on the leaders and health workers who contend with the worse of it. Serious concern wells up about workers and families upended as the economy takes a nose dive. We are all affected. We are all—as a planet—in this together. May we find our way through to a more cohesive and caring tomorrow.

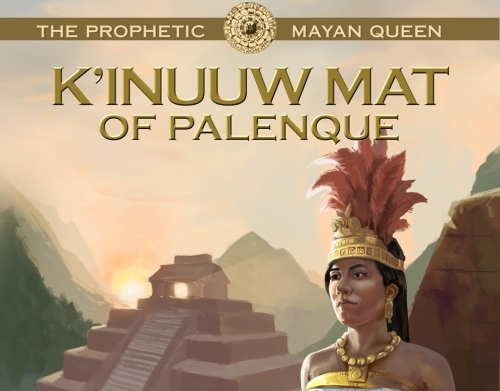

Chanticleer Book Reviews Semi-Finalist 2020

The Prophetic Mayan Queen is a Semi-Finalist in Contemporary & Literary Fiction

The SOMERSET Book Awards recognize emerging talent and outstanding works in the genre of Literary, Contemporary, and Satire Fiction. The Somerset Book Awards is a genre division of the Chanticleer International Book Awards (The CIBAs).

Chanticleer International Book Awards is looking for the best books featuring contemporary stories, literary themes, adventure, satire, humor, magic realism or women and family themes. These books have advanced to the next judging rounds. The best will advance. Which titles will be declared as winners of the prestigious Somerset Book Awards?

At the Authors Conference in Bellingham, WA, on April 18, 2020 the winners of all divisions of Chanticleer Book Reviews will be announced. It’s very exciting for my latest book to reach the semi-finalist stage! There are 16 semi-finalists in each division. I’ve long thought the names given for these divisions are humorous and entertaining, such as Chaucer Awards for Early HIstorical Fiction, Chatelaine Awards for Romance, Ozma Awards for Fantasy, Cygnus Awards for Science Fiction, Dante Rossetti Awards for Young Adult Fiction, Litle Peeps Award for Early Readers, and more.

Within a division such as Contemporary & Literary Fiction, authors need to choose among subcategories. After pondering this choice I selected two subcategories: Women’s Fiction and Magical Realism. The first is obvious, since the protagonist is a talented and strong girl who develops into a powerful, wise queen with a mandate to preserve her people’s heritage. The second was selected because the Mayan culture has deep themes of mysticism and inter-dimensional realities. Rulers, priestesses, shamans, and healers had frequent interactions with spirit beings such as goddesses and gods, elementals, and ancestors. To the Mayas, this was part of their normal world, so this kind of magic was very real to them.

The Prophetic Mayan Queen: K’inuuw Mat of Palenque has garnered other acknowledgement, such as a 5-star review by Seattle Book Reviews and several praiseworthy editorial reviews. Here’s hoping she wins the Somerset Award which comes with a great Prize Package with lots of publicity!

2020 Tucson Festival of Books – March 14-15

The Tucson Festival of Books is a community-wide celebration of literature. Offered free-of-charge, the festival exists to improve literacy rates among children and adults. Proceeds that remain after festival expenses have been paid are contributed to local literacy programs.

Started in 2009, this gathering of authors and publishers, marketers and sponsors, receives up to 135,000 visitors and features around 500 authors and presenters. Each year event typically includes special programming for children and teens, panels by best-selling and emerging authors, a literary circus, culturally diverse programs, a poetry venue, exhibitor booths and two food courts. Featured authors give talks in various buildings, while in the university mall there are booths for indie authors to meet fans and sell books in 2-hour time periods over the weekend. This year’s festival is March 14-15. You can see the schedule at: http://tucsonfestivalofbooks.org/

Friends have mentioned this book festival, but this is the first year that I’ll be participating. Just needing some warmth and sunshine after one of the most wet, cold, and grey winters in recent Oregonian memory. My books will be featured at the Indie Author Pavilion – Adult Fiction on Sunday, March 15, 2020 from 10 am-12 noon. If you’re in the area, stop by! I’ll be offering discounted book packages on the Mayan Queen series.

Ebook and print books available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and your local bookstore by order.

My last trip to Palenque was in 2012. Went to celebrate the 12-21-12 Winter Solstice when the Mayan Calendar ended a great cycle (Mayan Sun or Era) moving from the Fourth to the Fifth Sun. At least, that’s what many said . . . note that the world didn’t end as some predicted. The Mayas of course never said that–to them it was simply one great cycle ending and another beginning.

From Copan to Area 51

Intriguing sci-fi mystery begins in Copan Temple

This book caught my eye because of the Chamber of the White-Eyed Star God deep inside a major temple at Copan. With this Maya connection, I was drawn to read it, although slated genre was YA. I’m really glad I did! It’s the most enjoyable science-adventure-thriller that I’ve read in a long time. Below is my review.

The Coordinate 12-15-19

By Marc Jacobs 5*

High school seniors Logan and Emma are assigned a history project to explore the “how and why” of one of the great archeological mysteries of the world. Other student teams are assigned to Stonehenge, the Great Pyramid of Giza, and the Gate of the Sun in Tiwanaku, but Logan and Emma get the obscure Chamber of the White-Eyed Star God in Copan, Honduras. Immediately drawn in by the sequestering of data about the site, they launch on the adventure of a lifetime that takes them to Italy, The Vatican, Europe, and the Norwegian fjords. Unraveling the cues and threads of Columbus’ connections with the Copan temple and its astrological mysteries places them squarely in danger’s path, as other agents are also seeking these answers. The teenagers become entangled with U.S. Intelligence agents, international espionage information dealers, and two hapless professors who initially discovered the Star God’s chamber. Their efforts to solve the mysteries propel them into the highest levels of U.S. government and military secrets.

This is the best scifi thriller that I’ve read in a long time. It grabs you and immerses you in the teenager’s brilliant detective work to sort out connections and meanings between astrological clues, ancient sites, and historical figures. Some of the happenings may be far-fetched, but the author provides enough science to make them plausible. There are captivating descriptions of the ancient sites and contemporary places visited during the teen’s quest, along with background material that adds perspective. Just when things are getting obvious, totally unforeseen twists take place setting up more layers of intrigue. With exciting action and mind-bending theories, the plot engages our inner sleuth and challenges our problem-solving abilities.

The main characters are engaging and well-developed, the bad guys well-portrayed and hard to figure out at times. There is a sweet budding romance between Logan and Emma, though we are left with mysteries at the end, especially regarding Emma. Though given the genre of YA, this complex story will be enjoyed by most adults. A sequel is coming soon, and I’m getting it as soon as it’s released.